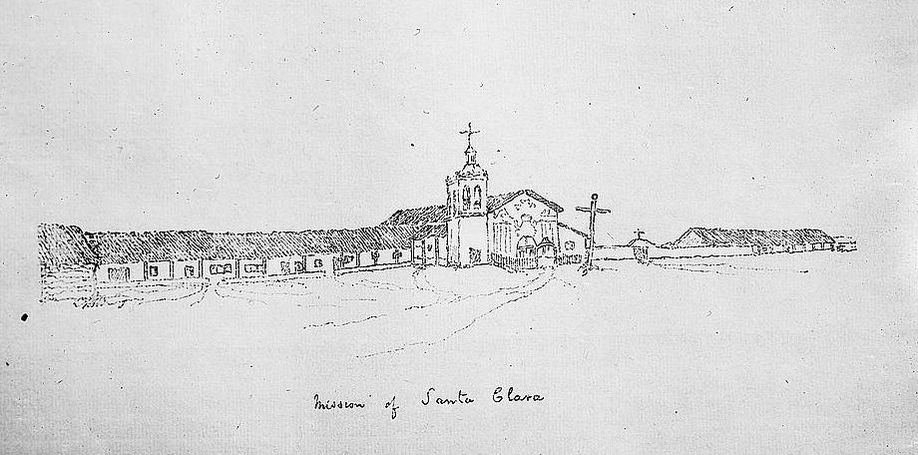

This two part article was published in the Martinez News-Gazette on 11/12/ & 11/19/2017Reprinted in two parts with special permission from Los Californianos newsletter, Noticias para Los Californianos Vol 49 No 4 October 2017. She is the niece of Salvio Pacheco (founder of Concord & Pacheco) and former partial landowner of the Alhambra Cemetery. Dr. Damian Bacich is a professor at San Jose State University and leading researcher of Californianos pioneers for the Potter’s Field Restoration Project: Historians frequently spend time building a narrative to organize the seemingly unrelated pieces of data they come across in their research. But often the beauty of historical research lies in uncovering the stories of so-called “ordinary” people, the individual dramas that resist easy categories or grand narratives. As a researcher of early California documents, I have always been drawn to such stories, and my most recent project involves the life of a woman named María Sylveria Pacheco de Coles, a Californiana who grew up at Mission Santa Clara. Out of the Shadows I came to know Sylveria as I was investigating the life of Fray José María Suárez del Real, the last Franciscan priest at Mission Santa Clara. Fr. Real (as his contemporaries knew him) arrived in Alta California in 1833, as a member of a group of Mexican-born Franciscans sent to replace Spanish priests in the northern missions. Before serving in Santa Clara, he was the resident missionary at Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Carmel (you can find my article on him in the current issue of California History). Like some other members of his cohort, Fr. Real was known as a colorful character, but he also gained a reputation as a person of dubious moral standards. Whether this reputation is deserved is open to debate, but he was a key figure during the tumultuous 1830s and 1840s in Alta California. While researching Fr. Real, I spent a good deal of time in the archives at Santa Clara University. There, Sylveria’s name appeared occasionally in mission records and other documents, especially during the 1840s and 1850s. I eventually came across a letter written in the early 1900s to historian Fr. Zepheryn Englehardt, in which Sylveria was accused of being the mistress of Fr. Real, and mother of his children. This, of course, piqued my curiosity, as it was directly related to the poor reputation that Fr. Real had acquired. As inflammatory as this allegation is, I was not able to find any information that would either confirm or refute it. Nevertheless, as I continued my work on Fr. Real, I kept notes on the information I found about Sylveria. What really caused me to turn my attention to Sylveria was an article from 1916 titled “The Passing of the Pachecos.” The piece appeared in the Overland Monthly, a turn-of-the-century literary journal focused on California and edited by author Bret Harte. The writer of the article, Harry Burgess, wrote about visiting Sylveria at the Pacheco family rancho in what is today Concord, California. The article depicts Sylveria as the lone survivor of a bygone age, a relic of an archaic, romantic past. In a mix of Spanish and English, Sylveria tells stories of her life growing up at Mission Santa Clara (“Days of heroism, sacrifice and joy!”), her later marriage to an American (“He was bad!”) and her property at the mission (“They took it from me . . . but it is mine!”). The article concludes by implying that Sylveria helped her American husband meet his end: “ ‘Then I sent him on a journey.’ The gesture accompanying the Senora’s [sic] word picture of the summary disposal of her Gringo consort had done credit to a Medici.” If the author truly met Sylveria Pacheco in 1916, as he claims, it would mean that she lived to be at least 105 years old. At that point, I began to seriously seek out information about Sylveria Pacheco. The fact that she had lived well into the twentieth century meant that not only had she seen the most prosperous era of the California missions, but that she had lived through the Mexican era, the US-Mexico War, and the annexation of California, long enough to witness the revival of interest in California’s mission and rancho heritage. Perhaps she could tell us something more about the lives of women in Alta California. The confirmation to my interest in knowing more about Sylveria’s life was when I presented a paper at the California Missions Conference at Mission Santa Inés in February of 2017. I received excellent feedback about my paper, and I was encouraged to pursue further research about her. Her Life What does the historical record tell us about Sylveria? She was born in the Pueblo of San José de Guadalupe (modern-day San José, California) on June 21, 1811. Records tell us that she was baptized María Sylveria Pacheco at Mission Santa Clara, just one day later. Like many Hispanic women of her time, she was given María as a first name, but among friends and acquaintances, was known by her middle name, Sylveria, sometimes spelled “Silveria.” Sylveria’s parents were Miguel Antonio Pacheco y del Valle and Juana María Sánchez de Pacheco. Miguel and Juana had a total of 12 children, of which Sylveria was the ninth. Sylveria’s mother, Juana, was born at the Presidio of San Francisco in 1776, the daughter of Anza Expedition members, and seems to have been only the second child baptized at the Presidio. Later in life, as a widow, she received a grant for Rancho Arroyo de las Nueces y Bolbones, which encompassed what would later become the town of Walnut Creek. Her Life Continued Sylveria was raised at Mission Santa Clara. Her early years coincided with the growth and prosperity of the mission under the direction of Franciscan padres José Viader and Magín Catalá. Viader was known as a vigorous and capable administrator, who left us a great amount of documentation about the life of the mission. His confrère, Fr. Catalá, was known as the “Holy Man of Santa Clara,” beloved by Californios and Indians alike. Together they oversaw life at Santa Clara for almost 30 years. Sylveria’s life took a dramatic turn in 1829, when she was 18 years old. According to mission records, her father, Miguel, was struck in the head by an ox, and died shortly thereafter. He was 74 years old at the time. Fr. Catalá also died in the same year. In February of 1832, Sylveria married a Prussian aristocrat named Karl von Gerolt. Gerolt had come to California to gather information about indigenous languages, and had been fascinated by the work of Fr. Felipe Arroyo de la Cuesta at San Juan Bautista. Karl tragically died only two months after their wedding. Sylveria, 21 years old at the time, was pregnant with Karl’s son Carlos. Little Carlos was born in October of 1832, but only lived until May of the following year. We know very little about Sylveria’s life in the 1830s, but in 1840 she requested and received a grant of a piece of land and a building she had been occupying at Mission Santa Clara. She justified her request by stating that she had been working for the mission for several years. Over the course of that decade, Sylveria became a mother to three boys: José María, born in 1845, José Osana, in 1847, and Valeriano (also spelled “Baleriano”) in 1850. She was not married at the time of their births, and the baptismal records do not say who their father was. At some point, most likely in the late 1850s, Sylveria married again, this time to an American, Charles H. Coles (sometimes spelled “Cole”). The 1860 census listed Coles as a farmer, and he and Sylveria shared a household in Contra Costa County, on the Pacheco family rancho. In 1860, according to records at Mission Santa Clara, she and Charles deeded her land back to the Mission Santa Clara, which was then home to the Jesuit Santa Clara College (later Santa Clara University).

By 1870 Coles was gone, and Sylveria was in Oakland, with her son José María, then 25 years old and working as a teamster. By 1880, however, she and her youngest, Valeriano, 29, were back on the family rancho in Concord, where she likely lived out her days, reminiscing on her intense and interesting life. After 1880, the historical record grows silent about Sylveria, until her profile in the Overland Monthly. Unanswered Questions Despite this information, there are still questions that remain tantalizingly unanswered. Among the most important are the date of her death and her final resting place. Did she really live to be over 100 years old? What became of Coles, her American husband? What about her sons, José María, José Osana, and Valeriano? Another important set of questions revolves around her property at Mission Santa Clara. In a letter conserved at the archives of Santa Clara University, Fr. John Nobili, the Jesuit priest who assumed control of the mission, mentions that Sylveria’s property was the old neophyte women’s residence. Is this true? In her petitions to Gov. Juan Bautista Alvarado, that fact is not mentioned. Nor have I been able to locate any written reference to the location of the neophyte women’s residence at Mission Santa Clara, although the existence of the men’s residence is well-documented. Furthermore, if Sylveria’s words in the Overland Monthly profile are to be trusted, she did not give the property to the Jesuits of her own accord, and believed it had been taken from her. Each piece of information brings up new questions. Thanks to the increased digitization of documents, I have been able to find a surprising amount of information starting with a simple online search. With online sources, however, it is doubly important to verify the information you encounter. For example, I learned of a burial plot under the name of Sylveria Pacheco at a cemetery in Oakland. The year listed was 1873. Nevertheless, when I phoned the cemetery, I discovered that the grave belonged to a three-day old infant. It was not María Sylveria Pacheco de Coles, but was this child somehow related to Sylveria? Another question to be answered. I also found another grave site with Sylveria’s name attached to it, this time on the website of the Potter’s Field Restoration Project (www.martinezcemetery.org), under the auspice of the Martinez Historical Society. A phone call to Joseph Palmer, a board director of the Martinez Historical Society, revealed that it was indeed “my” Sylveria Pacheco who had owned two lots of the Alhambra Cemetery in Martinez, but she is not buried there, since she was forced to sell them due to financial difficulties. You Can Help These two examples highlight how important it is to reach out and make contact with people when doing historical research. Since starting the Sylveria Pacheco project, a number of people have provided me with help and encouragement. They include Sheila Ruiz Harrell of Los Californianos, Sheila Benedict, archivist at Mission Santa Inés, and archaeologist Glenn Farris. Perhaps you, too, have some information about the life of María Sylveria Pacheco. Are you a descendent of Sylveria Pacheco or one of her sons? Do you know of anyone who is? Do you have any information about her final resting place, or that of Charles Coles, her second husband? Any such information would be of great interest to me and would help shed light on the life of this fascinating individual. I can be reached at [email protected], or through the California Frontier Project at www.californiafrontier.net. Judie & Joseph Palmer are two of the founding members of the Martinez Cemetery Preservation Alliance (MCPA) and the Potter’s Field Project. Both have a passion for discovery, history, genealogy, anthropology and archaeology. For more info, please visit our website MartinezCemetery.org. Do you have a Potter’s Field story to tell? We welcome any pictures or information regarding the Alhambra Pioneer Cemetery or its Potter’s Field. Please email us at [email protected] or call us at (925) 316-6069. |

AuthorsJudie & Joseph Palmer are two of the founding members of the Martinez Cemetery Preservation Alliance (MCPA) and the Potter’s Field Project. Both have a passion for discovery, history, genealogy, anthropology and archaeology. Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed