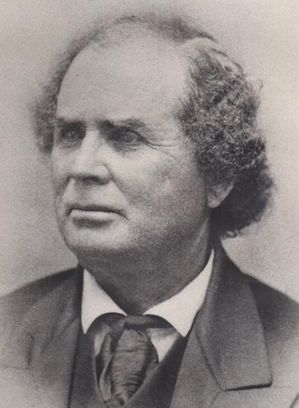

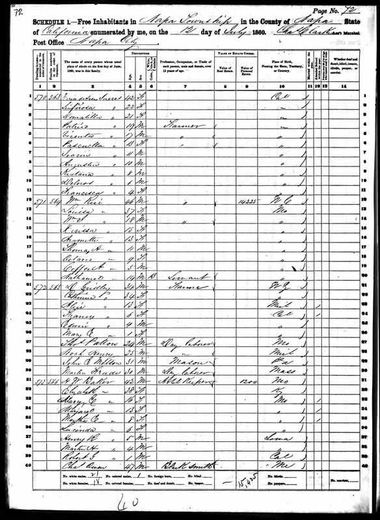

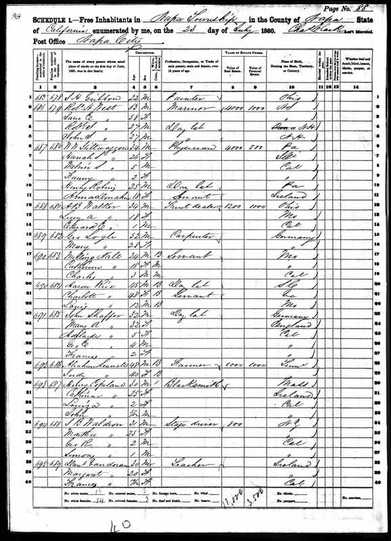

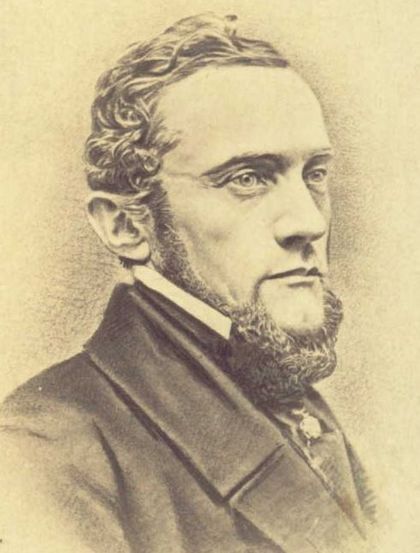

This Article was published in the Martinez News-Gazette on 9/3/2017 Napa Valley - view from the Oak Knoll Farm, Napa County Courtesy of Library of Congress Napa Valley - view from the Oak Knoll Farm, Napa County Courtesy of Library of Congress When last we wrote, Aaron and his family decided on freedom, but Nathaniel was still entrapped by William Rice. William, like any other post Southern slaveholder, would have many reasons for wanting to find a way to keep their slaves. California was perfect for year round farming of wheat due to its need for little water, rich soil and perfect temperature. Other motives were more acquisitive: low cost labor made profits higher. Post southerners also believed that pro-slavery democrats would remain in office and continue to loosely enforce California’s Constitution against slavery. Since the majority of slaves were prevented from becoming literate when they lived in the South, it was then easy for slaveholders to prevent them from knowing they were free. Many slaveholders promised their slaves freedom for a price. In Aaron’s case, he might have been given a garden plot to grow and sell his own produce. Or worked for someone else on his off day (Sunday) and kept the money. Or rented himself out under the Hiring-out System for a small portion of the money.  Portrait William Rice, Courtesy of the Friends of Rice-Tremonti Home Portrait William Rice, Courtesy of the Friends of Rice-Tremonti Home In California, many slaves were told of its constitution and laws regarding slavery via other free blacks or abolitionists, such as Rev. Thomas Starr King. Most likely it was Rev. King, who informed Aaron, his family, and the other slaves of their rights during that fateful meeting in April of 1860, that they were already free and didn’t have to purchase their freedom from William. The fact that Aaron’s wife Charlotte and father, Robert purchased land from William Russell on September 17, 1860 only a few months after their meeting, supports this theory. According to the account published in the History of Contra Costa County by W. J. Slocum & Co., William still felt resentment for Aaron’s exit, “In April, five of the six Negroes that Mr. Rice had brought across the plains with him, left him, and afterwards the last, with his son, wished also to severe his connection with his benefactor.” His Southern attitude can be further explained in C. W. Harper’s article, Black Aristocrats: Domestic Servants on the Antebellum Plantation, “Usually the white family looked upon desertion by a favorite domestic as a personal insult to the family.” In one case, Harper states, “Robert Phillip Howell's servant, Lovet, disappointed him more than any of them. “He was about my age and I always treated him more as a companion than a slave. When I left I put everything in his charge, told him that he was free, but to remain on the place and take care of things. He promised me faithfully that he would, but he was the first one to leave…””  1860 US Census listing Nathaniel with William Rice's Family 1860 US Census listing Nathaniel with William Rice's Family In 1860, it was a disunited time for California and our country, with the 1860 U.S. Census caught in the middle of it. Dr. Olson-Raymer states, “By 1860, California's black population was 4,000. After the constitutional ban on slavery and the admission of California as a free state, blacks in California were technically free. However, the California Fugitive Slave law of 1852 left blacks in an ambiguous status - they were neither slave nor citizen in California.” Local and congressional favoritism would flow from the results and handling of the census. U.S. Marshals would assign assistant marshals to canvas the population in their territories. Melissa Jacobson accurately describes California census taking in her article, The “MO” 1850s Census Mystery (published in the Martinez News-Gazette, December, 2012), “Until 1960 the census takers went door to door, and in 1852 it was done this way as well -- except on horseback and probably by boat.” From the US Census taken on July 12, William is listed as 46, living in Napa City in Napa County, farmer, with a personal estate of $14,225. Additionally listed within his household are his family and Aaron’s oldest son Nathaniel 14 as servant.  1860 US Census Listing Aaron, Charlotte, & Lewis Rice 1860 US Census Listing Aaron, Charlotte, & Lewis Rice From the US Census taken on July 23, Aaron, his wife Charlotte and their youngest son Louis are also counted by name for the first time, living in Napa with no personal wealth listed. They are listed as Aaron 45 day laborer; Charlotte 48 servant; Louis 12 (who was actually 10). According to an essay by Diane L. Magnuson at IPUMS USA, “The pre-eminent concern for discussants at the time was whether partisan loyalties would lead these officials to falsify returns to affect apportionment, swelling the count in areas where their parties held sway and purging the rolls elsewhere.” Due to pro-slavery Californians, along with the effects of the Fugitive Slave Law still lingering, concerted efforts were made to affect the results by attempting to limit the number of African Americans counted and other such actions. Perhaps this explains why we cannot find Robert and Dilcy’s enumeration, as they might have remained with William (to protect their grandson) who prevented their Census inclusion. It is our belief that after becoming free, Aaron’s family decided to continue working for William and his family for payment of services rendered and to prevent the California Fugitive Slave Law being used against them. However, William refuses to pay Nathaniel. Believing that his family was done with William’s bondage contracts, Aaron finds the courage to legally challenge him, despite the law preventing their testifying against a white man, the looming fear of potential imprisonment, or excessive fines.  Portrait Judge Pulaski Jacks Courtesy of his family Portrait Judge Pulaski Jacks Courtesy of his family The August 20, 1860 Napa Register writes, “Almost an “Archy Case” at Napa.--The Napa Reporter says: On the 10th August, Aaron Rice, a colored man, swore out a habeas corpus, declaring that his son, a boy of 17 or 18 years, was unlawfully restrained of his liberty by William Rice, who resides in this valley, and that the latter claimed said boy as a slave. The writ was granted by Judge Jacks, and Mr. Rice arrested.” Aaron could not have found a better judge than the Honorable Pulaski Jacks. As written previously, Delilah Beasley describes in her 1819 book, The Negro Trail Blazers in California, “California Reports, No. 2, p. 424: “By the set of April 20, 1852, the power of hearing and determining writ of habeas corpus is vested in the Judge of every court of record in the State. The final determination is not that of a court, but the simple order of a Judge, and is not appealable from or subject to review.”  Pulaski Jacks Business Card Pulaski Jacks Business Card Judge Jacks was a Republican and thereby most likely an abolitionist sympathizer born in the free state of New York on December 14, 1812. As a young man he started out selling watchcases and jewelry. He brought his family to California during the gold rush to continue his occupation as a jewelry merchant and started a business in San Francisco, “Pulaski Jacks & Co.” with his two brothers, William and Hamlet. According to the U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880, ending the year in June 30, 1860, Judge Jacks owned 100 acres of farmland in Napa. With William’s immediate arrest, Aaron Rice becomes the first of four known formally enslaved African-Americans to charge their former masters in court in the great State of California… Judie & Joseph Palmer are two of the founding members of the Martinez Cemetery Preservation Alliance (MCPA) and the Potter’s Field Project. Both have a passion for discovery, history, genealogy, anthropology and archaeology. For more info, please visit our website MartinezCemetery.org. Do you have a Potter’s Field story to tell? We welcome any pictures or information regarding the Alhambra Pioneer Cemetery or its Potter’s Field. Please email us at [email protected] or call us at (925) 316-6069. |

AuthorsJudie & Joseph Palmer are two of the founding members of the Martinez Cemetery Preservation Alliance (MCPA) and the Potter’s Field Project. Both have a passion for discovery, history, genealogy, anthropology and archaeology. Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed