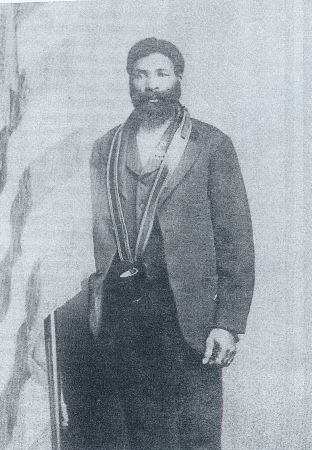

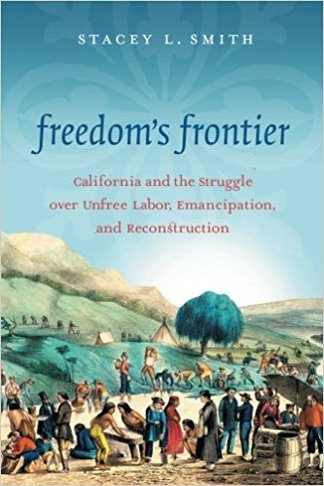

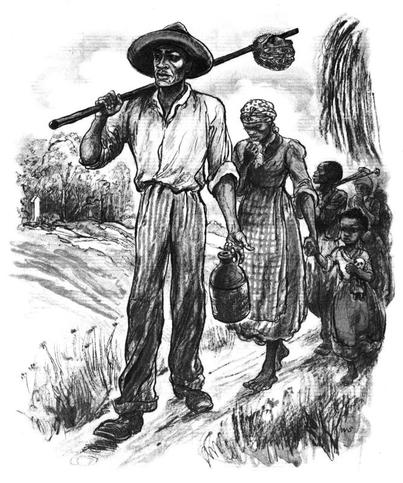

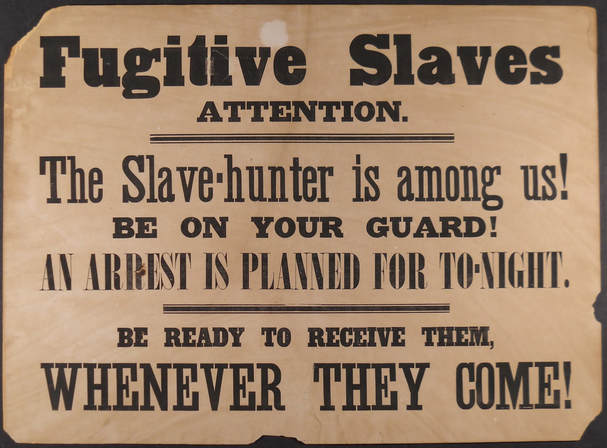

This Article was published in the Martinez News-Gazette on 7/30/2017By JOSEPH & JUDIE PALMER Special to the Gazette  When last we wrote, in April of 1860 William Rice was searching for ranch land in Walnut Creek, while Aaron was tending to William’s farm in Napa. During this time, Rev. King, (whom we wrote about extensively in our last column), visits Aaron. The only account we have of Rev. King’s visit is from John Grider in Delilah L. Beasley’s 1819 book, The Negro Trail Blazers in California, “Rev. Thomas Starr King went to a ranch near Napa, California, and emancipated a number of slaves. Among the number were the following named persons: Aaron Rice, Old Man Sours, Wash Strains, Old Man Sydes. Their names were given to the writer by a Mr. Grider, who was a member of the Bear Flag Party. He said that these persons were the slave-property of a gentleman in Walnut Creek, and had been taken to Napa to continue as slaves, when the word reached Rev. Thomas Starr King, who proceeded to go to this place and emancipate them.” Whether Rev. King actually emancipated them or just informed the men of their rights is unknown.  John Grider Courtesy of Sharon McGriff-Payne John Grider Courtesy of Sharon McGriff-Payne Mr. Grider on the other hand had received his own freedom earlier through mining. Delilah Beasley states, “Mr. John Grider came to California in 1841, with Major Barney, Dick Gardner, and Major Wyeth, owners of fine horses. They came from Silver County, Tennessee, through Mexico to California. He acted as horse trainer for the party. After reaching California, Mr. Grider decided to follow mining. He worked in the mines at Murphy’s Diggings, which was located seventy miles from Stockton. He was very successful and paid Major Wyeth $800 to bring his mother to California. Upon her arrival, he purchased her a home in Marysville, where Mrs. Caroline Grider spent the remaining days of her life. Mr. Grider has practiced as a veterinary surgeon in Vallejo almost continuously since 1851.” To give more understanding and context for what happens next for Aaron and his family, more information regarding this period is needed. Slaveholders like John Grider’s were rare. According to the National Humanities Center’s Toolbox Library, The Making of African American Identity: Volume 1 1500-1865, “Opportunities for most enslaved African Americans to attain freedom were few to none. Some were freed by their owners to honor a pledge, to grant a reward, or, before the 1700s, to fulfill a servitude agreement… Many ran away to free territory, and some of these "fugitives" succeeded in avoiding capture and forced to the South… A rare option was "self-purchase" (the term itself revealing the base illogic of slavery). In 1839 almost half (42%) of the free blacks in Cincinnati, Ohio, had bought their freedom and were striving to create new lives while searching for and purchasing their own relatives.”  Courtesy © 2013 The University of North Carolina Press Courtesy © 2013 The University of North Carolina Press California’s Fugitive Slave Law of 1852 dramatically effected African-Americans. Charles Perkins had come to the gold mines of California on his father’s money and failed. With enough in his pocket for himself, he returned home to Mississippi without his three slaves in the spring of 1851. From BlackPast.org, historian Stacey L. Smith writes in her article, Pacific Bound: California’s 1852 Fugitive Slave Law, “Like other slaveholders who hoped to keep their bondpeople from running away in the mines, Charles Perkins struck an informal emancipation bargain with the men. If the three slaves worked faithfully for six months under the supervision of one of Perkins’s friends, they would earn their freedom. Accordingly, Perkins’s friend released the men in November of 1851.”  Capturing Fugitive Slaves circa 1856 Capturing Fugitive Slaves circa 1856 The three freed slaves began a business of their own and became very successful. Unfortunately, their freedom was short lived. During the night of April 31, 1852, Stacey writes, “While the three men slept, a group of armed whites broke into their cabin. The invaders tied up the black men, loaded them into their own wagon, and hauled them to Sacramento using their own mule team. There, a justice of the peace pronounced the men to be fugitive slaves and ordered their deportation back to the Slave South.” She continues, “Crabb and his southern-born allies in the proslavery branch of California’s Democratic Party pushed for a state fugitive slave law that would allow masters to hold the slaves who they had brought to California before statehood and take them back to the South. Any enslaved person who resisted this process would be criminalized as a fugitive slave.”  Courtesy California State Library Courtesy California State Library Crabb’s bill passed the assembly in 1852, but was challenged by northern senators in the senate. Smith writes, “Southern-born Democrats managed to outmaneuver Broderick and won moderates to their side by appending a “sunset clause” to the bill. This clause stipulated that masters would have only one year to claim their slaves and remove them from the state. They could not hold slave property in California indefinitely. Optimistic that the new law struck a careful balance between protecting slaveholder rights and preserving California’s antislavery constitution, moderates joined proslavery men in passing the law. It went into effect on April 15, 1852.” A small African-American community in Sacramento funded and hired a white lawyer to defend and release the three, but to no avail. Beasley writes, “California Reports, No. 2, p. 424: “By the set of April 20, 1852, the power of hearing and determining writ of habeas corpus is vested in the Judge of every court of record in the State. The final determination is not that of a court, but the simple order of a Judge, and is not appealable from or subject to review.””  California Supreme Court SF (1852-1853) Courtesy of the CSCHS California Supreme Court SF (1852-1853) Courtesy of the CSCHS Smith writes, “Once the men got their day in court, a proslavery mob intimidated the presiding judge and he found in favor of the slaveholder. With financial backing from free African Americans, Cole and his colleagues appealed to the California Supreme Court… Hugh C. Murray of Missouri and Alexander Anderson of Tennessee, the two justices who presided over the case of In re Perkins were southern-born Democrats. They ruled that the fugitive slave law was, in fact, constitutional… The court found in favor of the slaveholder. Perkins’s agents took custody of the men and departed for Mississippi.”  Fugitive Slave Family Walking Fugitive Slave Family Walking Smith finishes, “Even free African Americans could easily fall victim to kidnapping and fraud because California’s black codes prohibited them from testifying against whites in state courts. Most importantly, the law’s sunset clause proved malleable in the hands of proslavery politicians. In 1853, and again in 1854, the state legislature voted to extend the fugitive slave law another year. Slaveholders had until the spring of 1855 to claim and remove their slaves, making enslaved people vulnerable to deportation five or six years after most had arrived on California soil. Newspapers reported stories of nearly two dozen slaves arrested and sent back to the South between 1852 and 1855. Even after the lapse of the fugitive slave law in 1855, masters informally held slaves in California until 1864.” Aaron would have heard about this case and others like it and therefor carefully considered his choices and their potential impact on his family and himself. The other three men it is safe to assume fled as no later record of them can be found. Aaron and his family chose freedom, and to fight back. However Nathaniel (Aaron’s oldest son) was still entrapped by William.

Special Thanks to Historians and Authors: Stacey L. Smith, Sharon McGriff-Payne, Alexandria Brown who graciously gave generously of their time and research to insure the accuracy of Aaron's and his families story. Thanks also to BlackPast.org, the California State Library, the California Supreme Court Historical Society, Starr King School for the Ministry, The University of North Carolina Press, for their generous contributions. Judie & Joseph Palmer are two of the founding members of the Martinez Cemetery Preservation Alliance (MCPA) and the Potter’s Field Project. Both have a passion for discovery, history, genealogy, anthropology and archaeology. For more info, please visit our website MartinezCemetery.org. Do you have a Potter’s Field story to tell? We welcome any pictures or information regarding the Alhambra Pioneer Cemetery or its Potter’s Field. Please email us at [email protected] or call us at (925) 316-6069. |

AuthorsJudie & Joseph Palmer are two of the founding members of the Martinez Cemetery Preservation Alliance (MCPA) and the Potter’s Field Project. Both have a passion for discovery, history, genealogy, anthropology and archaeology. Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed